Not thinking about race is a luxury I don’t have.

I’m at least as much a journalist as I am an artist. Most folks would say I’m more of the former than the latter.

I’m also the son of parents who endured a familiar strain of American racism—that of white against Black—systemic and personal. Edith, my mom, born in 1936, attended integrated public schools in Queens, NY, but confronted bigotry as she pursued a career in teaching in Long Island and New York City. She was the “first Black” in many positions, and she has both scars and wisdom from these experiences.

Eddie, my dad, born in 1928, never recovered from the government’s seizure of his family’s land in York County, VA, in 1943 to build a Seabee training base. His entire majority-Black community was dispossessed. Resettlement options open to whites were closed to Blacks because of Jim Crow. My father, the grandson of enslaved people who in freedom helped found the village where he was born—and from which he was evicted—served during the Korean War just two years after President Truman’s desegregation order. While stationed in Germany, Eddie fought no battles with Germans, but many against racist white soldiers from the Deep South who resented him—his sergeant’s stripes, his ability to speak a smattering of German, and his popularity with the local (white) ladies. He came home to the same Jim Crow–sick nation in 1952.

My parents passed on this history to me and my sister—my father with a bone-deep bitterness; my mother with caution, weariness, and an iota or two of hope for a better future for her children. They sensitized me to racial prejudice and white supremacist attitudes, even before I had a name for these perceived forces and threats. I wake up each day knowing that my mere Black presence will frighten or offend some non-Black person. It happens in Richmond, in New York, in Cleveland—all cities with plenty of Black folk—when I enter spaces not typically frequented by Black people. Are my reactions perceptions or misperceptions? Sometimes it’s crystal clear, sometimes not. The point is, not thinking about race is a luxury I don’t have.

For me, American democracy is more of a promise, too often broken when made to people of color, than a lived reality—or a real possibility. In some places it seems unattainable. I felt this keenly in Cleveland and about Cleveland. On paper/in pixels, the city’s poverty rate is staggering. The poverty rate among African Americans is even more shocking. Many times a day, I ask myself questions that may seem basic, but that clearly have not been answered, in Cleveland or anywhere else: How can such privation and deprivation exist in this rich nation with its rhetoric of equal opportunity? Why do racially discriminatory systems, patterns, and practices endure?

“American democracy is more of a promise, too often broken when made to people of color, than a lived reality—or a real possibility.”

These photos are expressions of my anger, cynicism, hope, and so many other feelings about the opportunities available to Black people in this democracy, this nation that still cannot fully contend with its ugly past; where so many white citizens are wedded to myths and delusions of white supremacy that are toxic to the physical and mental health of people of color, and to the health of our country. I worried—and still worry—that my photos would be too depressing, too dispiriting.

East Cleveland, OH—Memorial for Vincent Belmonte, 19, killed on Tuesday, January 5 allegedly by a member of the East Cleveland Police Department as Belmonte was driving his girlfriend to work in a borrowed car.

I visited Cleveland three times. COVID-19 was a factor, a presence on all of these trips and had a profound effect on how I made photos—mostly from a distance. In October 2020, I visited during early voting in a presidential election that pitted the incumbent, our nation’s most antidemocratic and racist president in modern times, against a sane, if uninspiring, politician who was human. Along with many millions of others, I was terrified that my countrypeople would keep him in office despite his demonstrable and toxic antipathy to people like me and those I love—Black, Muslim, Latinx, unrich, queer, etc. It was a scary time. Nineteen-year-old Vincent Belmonte was killed by police in East Cleveland my first day in town in January 2021. The January 6 insurrection happened the day after. During my third stay, Daunte Wright was shot and killed by police in Brooklyn Center, MN. I am embarrassed to write that the details of his killing, so clear at the time, are now hazy. Wright’s story blends with those of the other African Americans whose lives were taken by law enforcement officers.

In spite of the awfulness I describe above, I found hope and affirmation from the folks at University Settlement, Famicos, Twelve Literary Arts, Kirk Middle School, Shaw High School—and even the folks at the Garfield Heights Funeral Home. They were doing what they do every day, serving their community. Proudly. To me, they are the bulwarks of our creaky democracy, the folks who grind through obstacles—structural, situational, whatever—to get things done for those around them.

Lucas Memorial Chapel, Garfield Heights, OH—Operations at the African American-owned funeral home.

My faith is in them, their dedication, tenacity, patience—and their palpable achievements. By documenting these people and the work they do I hope to convey my hope that democracy will be realized by and for the people now trapped at its margins.

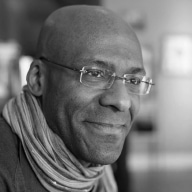

Brian Palmer

Journalist & Photographer