How much poison can our democracy withstand?

I was 10 in the fall of 1962 when the San Francisco Giants and Los Angeles Dodgers tied for the National League pennant and were to meet in a three-game playoff. Unhappily, our TV was broken and my parents couldn’t afford to fix it but they agreed to let one of my brothers and me stay a few days with two elderly great aunts who lived on the other side of our town of Fremont, Ohio. I was especially excited to watch one of my heroes, the Giants’ star Willie Mays, who played baseball with greater skill and enthusiasm than anyone.

As it turned out, events far from the ballfield intruded. While Mays dazzled the Dodgers, a man I had never heard of, James Meredith, was trying to enroll in the University of Mississippi and become the first Black American to do so. The university and the state repeatedly tried to block him. Whites rioted. A reporter and a bystander were killed. The nation was riveted.

All of this entered America’s homes through the evening TV news, which was a staple at our aunts’ house. During a broadcast of the turmoil surrounding Meredith, one of my aunts remarked, “I just don’t see why he has to go there and cause all that trouble.”

Her words hit me like a slap—for the simple reason that Meredith had the same color skin as Willie Mays. If Meredith could not attend that school, then neither could my hero, and the unfairness of that was obvious even to my young mind.

It took the legal and military power of the federal government to open that door for Meredith and those who followed him. Racism had long since shriveled the hearts of the men running Mississippi. They did not worry about electoral consequences for their acts because they continually appealed to the worst fears and racial hatred of many whites and because they used the law to control who voted.

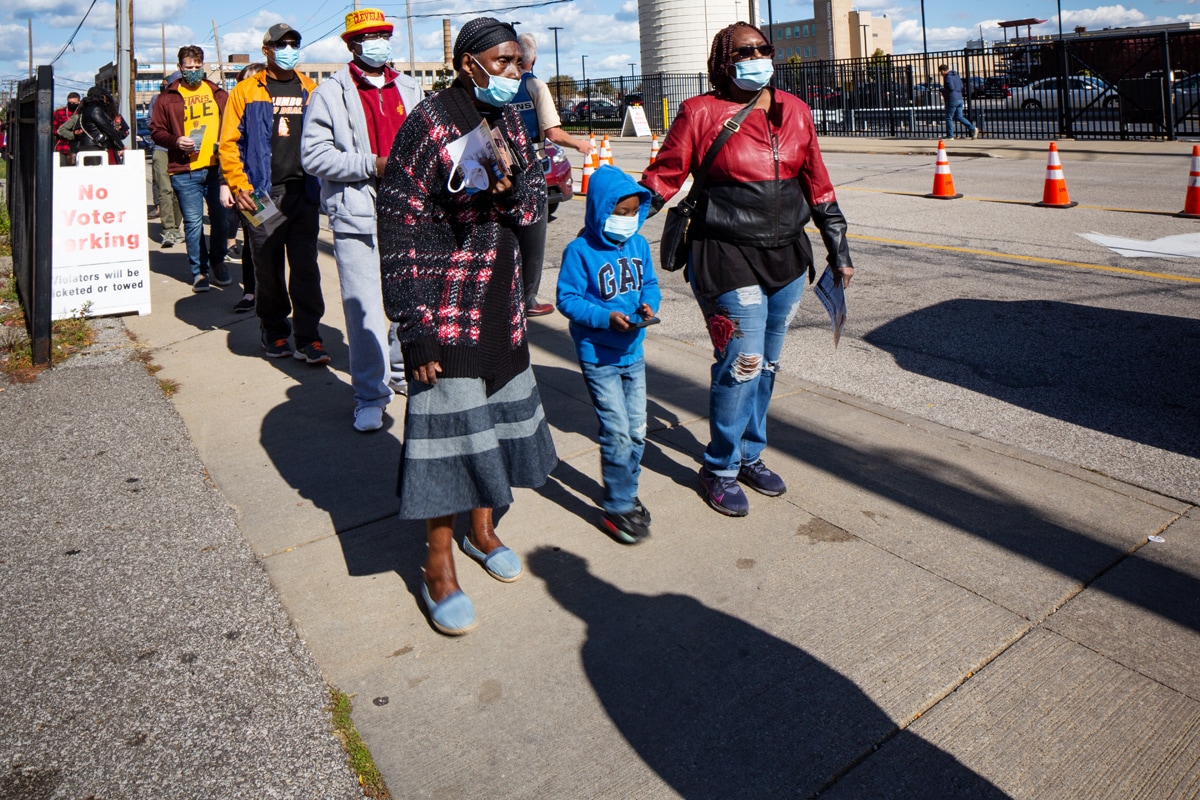

Cuyahoga County Board of Elections, Cleveland, OH—Early voting and ballot drop-off at the one early voting site in the county.

So, here we are nearly 60 years later struggling yet again with similar issues. The challenge of this moment is once more free and fair access to the ballot box. This time it is not Democrats setting up the barriers; it is Republicans. This time it is not a battle focused primarily in the South; it is nationwide. This time the racial dimension of the battle is less overt but the same ultimate question looms: What sort of country do we want America to be?

Do we want a democracy that keeps striving to live up to its founding ideals? Or are we willing to let an elite minority continue to distort the democratic process in order to cement its hold on power?

Their democracy-corrupting weapons are many: Torrents of unaccountable cash from unknown sources. Extreme gerrymandering. Outrageous lies about voting fraud, stoking fears that elections are being stolen. Suppressing the turnout of low-income, elderly and Black and Brown voters by making it harder and less convenient to cast a ballot.

The right to vote is the very essence of democracy. Throughout our history we have gradually expanded that franchise but each expansion followed a long struggle. Now, as the country’s demographics are evolving to become less white, the Republican Party has grasped for ways to seize or maintain control of power, even if it means undermining the right to vote.

“The right to vote is the very essence of democracy.”

Donald Trump was a godsend to these anti-democracy forces because he is uniquely unmoored from truth and from any respect for the democratic system. When he could see that he was losing his grip on power, he began shouting the Big Lie that the election would be stolen from him. He has not stopped. The Big Lie fueled the murderous insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6. And even more ominously, it is being wielded by most of the Republican Party to justify state-by-state restrictions on voting, including in Ohio.

Four out of five Republicans have swallowed the Big Lie. Trust in the fairness of elections has been shaken. Republican Congresswoman Liz Cheney, daughter of the former vice president and one of the few members of her party to stand up to Trump, quite accurately wrote in May, “The 2020 presidential election was not stolen. Anyone who claims it was is spreading THE BIG LIE, turning their back on the rule of law, and poisoning our democratic system.”

How much more of that poison can our democracy withstand?

American democracy has always been imperfect. We have rid our Constitution of some of the founders’ compromises but we still live with others. In addition, societal supports for the constitutional order are weaker. Institutions of all kinds have less legitimacy. The media information sources that we shared in prior eras are now fragmented and some are mere propaganda. And now a major political party has become a cult in thrall to a megalomaniacal liar. The most dire warnings about the threats to democracy no longer seem far-fetched. It now seems possible that a Republican-controlled Congress could refuse to certify the results of a future election if the American people choose a Democrat.

Yet, as a wise man once said, the solution to the problems of democracy is more democracy: More people engaged as active citizens with their communities and country. More avenues for that engagement. More accountability for lying, for inciting division and animosity. More respect for facts and truth. More people voting.

These are not easily achieved but all of us—including foundations—can help to move the country toward them. By being vigilant and active citizens. By organizing with others. By demanding truth and calling out lies. By advocating for policies and candidates in support of democracy. By standing with those who are targets of hatred and victims of prejudice. And as long as there are elections—free and fair elections—there is hope.

That hope, that faith is captured in the photo essay featured in this annual report. Brian Palmer, an award-winning photographer and journalist, portrays Clevelanders exercising their citizenship rights even with the nation in the grip of a pandemic. The fact that voting turnout increased at such a time is testament to the captivating appeal of democracy. This is what democracy looks like.

Cleveland, OH—Early voting at the Cuyahoga County Board of Elections; Shooting Without Bullets wheat pastes posters of the late Stephanie Tubbs Jones, former U.S. Representative (11th Congressional District)—“also the first black woman to become a judge of Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court, as well as the county’s first black prosecutor”—on the outside walls of the ACLU Ohio.

As I think back, I realize the turn my life took on that day in the fall of 1962. It began the never-ending process of opening my eyes to a world of issues and injustices beyond my narrow direct experience. It helped to set me on my own course of trying to live out active and constructive citizenship. A career embracing journalism, politics, government, nonprofits and philanthropy has given me countless opportunities for engagement. I loved them all but no role has been more gratifying than being at this incomparable institution for nearly two decades. It will soon come to a close. The time for transition to new leadership will arrive when I retire at the end of 2021. I owe endless thanks to our trustees for their wise insights and their unwavering commitment and backing; to my staff colleagues for the passion, conviction and dedication they always bring to our work; to our many grant partners who undertake the inspiring efforts I have been honored to help support; and to Cleveland, which has been and will remain my favorite place from which to face the world.

New paths await.

David Abbott

President